In June 2020, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) released the Global Rights Index 2020, a report on workers’ rights in 139 countries. The report painted a bleak picture for working people across the globe, most of all in the ten worst countries for working people. That list includes Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Honduras, India, Kazakhstan, The Philippines, Turkey, and Zimbabwe.

Many countries on this list have also been identified as large military spenders by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI) Military Expenditure Database. Furthermore, the overlap of human rights abuses and militarization is all too common and can be a recipe for violent conflict. Below, the cases of each of the ten worst countries for working people are elaborated upon and links are drawn between human rights abuses and military spending, with the goal of identifying larger trends. While the complete picture in any of the given countries is undoubtedly more complicated than the analysis below allows, the summaries underline key points of connection between militarization and human rights violations.

Bangladesh

The ITUC report highlights violence, mass dismissal, and regressive laws as the main sources of worker repression in Bangladesh. Over 50 striking workers experienced violence at the hands of police, with thousands more losing their jobs and over 500 facing criminal charges. Simultaneously, the Bangladeshi government spent 1.3% of GDP on the military – 9.7% of all government spending in 2019. The police themselves have been militarized and connected to the violation of human rights within the country.

Brazil

In Brazil, threats, intimidation, violent repression, and murder are all responses to strikes and demonstrations for workers’ rights. Brazil is the 11th highest military spender globally, making up 1.4% of global expenditure (over half of all South American spending). The strongman tactics and policies of President Jair Bolsonaro are clear and present in both matters – in which all actions rely on and can be solved by threats and violence; unfortunately, his sense of “law and order” does not extend to the extrajudicial killings of union leaders.

Colombia

Colombia saw the assassination of 14 union leaders between January 2019 and March 2020, among other concerning actions against workers’ rights advocates. ITUC highlights the under-resourced and dysfunctional justice system in the country as one reason why such crimes have gone unpunished; meanwhile, Colombia spends 3.2% of its GDP on the military, the 25th highest in the world. While domestic conflict continues to plague Colombia, a functioning justice system is essential; one must believe that Colombia could reduce its military expenditure to address other issues related to human security, such as the assassination of union leaders.

Egypt

Egypt maintains strict obstacles to union registration, and strikes have been met with state repression including arrests of participants. In one case, 26 shipyard workers were sentenced by a military court to one year of jail and a 2,000 Egyptian pound fine. While SIPRI data reports 2019 military expenditure as 1.2% of Egypt’s GDP, these figures are “highly uncertain” and likely a severe underrepresentation of actual spending. Given that the country continues to be run by a former general (who was also at one point the Minister of Defense and Director of Military Intelligence), it is clear where Egypt’s priorities are. For a truly stable society, President Al-Sisi’s government should focus on human rights.

Honduras

In Honduras, union-busting and death threats against workers are commonplace, with nearly no action taken by the government. In fact, military police fired live bullets at a Chiquita picket line. This is commonplace in Honduras, where “military-affiliated death squads” have been accused of killing activists in the country, such as environmental activist Berta Cáceres, or even in the supposed enforcement of the Covid-19 lockdown. While military spending accounts for 1.6% of the country’s GDP, it is clear the government and military are more interested in protecting their own interests than defending human rights.

India

India made the ten worst countries for human rights for their regressive laws, brutal repression of strikes, and mass dismissals of workers – including one case of 48,000 employees being let go, by a government corporation. India is also the third largest military spender on the global level, spending 2.4% of GDP on the military in 2019, and the biggest arms importer in the world. Given India’s economic heft and its position as the world’s largest democracy, these conditions reveal the contradictions found in the Indian government; human security is given an undervalued position when compared to the role of the military.

Kazakhstan

The ITUC report characterizes the repression of trade unions in Kazakhstan as “an orchestrated state policy to weaken solidarity,” including severe obstacles to union registration and the prosecution of union leaders. While military spending was at 1.1% of GDP in 2019, Kazakhstan experienced one of the largest increases in expenditure from the previous year. Political repression and human rights abuses in Kazakhstan are commonplace and have been raised as concerns by many groups. Kazakhstan’s leaders need to reconsider their priorities.

The Philippines

In the Philippines, the ITUC report makes clear that there is indeed a connection between the military and trade union repression – illustrating the case of a Coca-Cola union in Bacolod City, where two men “identifying themselves as military officers…denounced the union and threatened that the government ‘had ways of silencing troublemakers’.” In another case, the military accused a union leader of illegal possession of firearms and explosives. Paramilitary groups that are not officially part of the military (but have equipment) are also known to be involved in illegal operations in the country. While the country spends 1% of GDP on the military, it is clear that this money goes to funding the repression of human and workers’ rights.

Turkey

The crackdown on civil liberties that has been ongoing since the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey has included repression and prosecution of trade unions. At the same time, Turkey remains the 16th highest military spender in the world, with over 2.7% of GDP going to the military in 2019 – that’s over 1% of the global total, and an 86% increase since 2010. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s authoritarian tactics – including the heavy emphasis on military strength and union busting practices – are discouraging signs for democracy and democratic institutions in the country.

Zimbabwe

Union members in Zimbabwe have suffered violent attacks, threats, and prosecution, particularly the leaders of the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU). While, interestingly, Zimbabwe’s military spending decreased by 50% from 2018-2019, the nation’s central troubles – economic, political, and social – continue to inhibit the freedoms enjoyed by citizens, and workers in particular. It begs the question – military spending was significantly lower, but where did this money go instead? Demilitarization should create a peace dividend that improves the lives of Zimbabweans – including in their labor rights.

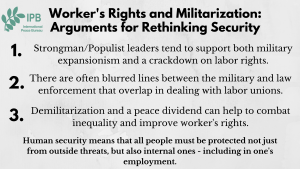

What we learn from the above analysis is that the ties between military spending and workers’ rights are complicated, multi-faceted, and varied. Nonetheless, there are important common threads that must be elaborated:

- Political crises are present in all countries in some form, many cases with a strongman or populist leader at the helm who has legitimized themselves and their leadership through emphasis on law and order, military strength, and economic development. While some of the list had very high military spending, this was not directly connected to repression of trade unions; however, all countries have leaders who are stark defenders of the military and strongman policies.

- Links between police forces and the military are often blurred or may include unofficial groups, such as para-military groups. Many of the countries either had military directly involved in the repression of trade unions or indirectly through the militarization of police forces, military courts, or groups whose exact connection to the government remains vague but who have military-grade equipment.

- Social and economic crises are present in most, if not all, the ten countries. Inequality is high and the distance between elites and workers is certainly a factor. Most countries saw either a large or moderate increase in military spending from 2018-2019, while a couple remained constant and very few saw decreases to military expenditure; even in the case of the latter, it is not sure where this money went. Demilitarization could provide a peace dividend to bridge the gap between the wealthy and the rest of society and lead to more fair societies in which workers’ rights are given a higher priority.

At the end of the day, the central concern in all these points is human security. Human rights abuses and the militarization of societies pose severe risks to security and could escalate tensions within any of the countries on this list – many of which are already in states of fragile peace or even outright conflict. These countries and so many more should take these points as a warning sign and evidence of the failure of the traditional understandings of ‘security.’ As a result, policies of demilitarization and arms control could ensure a de-escalation of tensions both domestically and abroad while providing a peace dividend to the larger society. Furthermore, the United Nations emphasizes the importance of human security considerations in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Given the pivotal moment we currently find ourselves in, it is crucial that we rethink what security really means.

Download the PDF file here.

Written by: Sean Conner, Assistant Coordinator for the International Peace Bureau